TITLE IX: Title Written, Story Unfinished

The 50th anniversary of Title IX reveals long-term impacts.

At 5:00 a.m., while many students are still in bed, Grace Ciaramitaro (12) can be found at the pool, practicing her freestyle or breaststroke. After Ciaramitaro’s one-hour practice, she heads to school, which is followed by another two-hour swim practice and a 45-minute workout.

She does all of this work in hopes to swim at a Division One collegiate level program. It’s a dream that is only possible today because of the passing of Title IX 50 years ago.

What is Title IX?

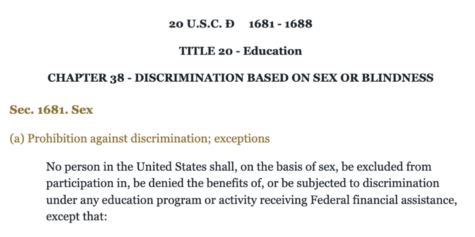

Title IX, also known as the Education Act Amendments of 1972, is legislation that bars discrimination against a person based on their sex in any education program that receives federal financial assistance. When it passed, the legislation opened up a plethora of opportunities for female high school and college students not only in athletics but also in universities, colleges and in the workplace.

When Title IX was passed by Congress and signed by President Richard M. Nixon, it was the second of three landmark decisions focused on women’s rights passed in 1972 and 1973. Title IX is the only decision out of the three still remaining.

The new legislation requires schools to provide girls and boys equal opportunities, from the provision of equipment to equal access to locker rooms.

To implement equality in schools in the fastest way possible, schools were given three options for ways to demonstrate compliance with the new law: “proportionality,” “progress” and “satisfied interests.”

Through “proportionality,” girls receive the same percentage of athletic opportunities as the percentage of girls in the student body. “Progress” directs schools to add new sports for girls on a regular basis, expanding the options available to girls. “Satisfied interest” requires schools to ask female students what sports they are interested in and to add those sports in the future.

The growth resulting from Title IX is remarkable: according to the Women’s Sports Foundation, the 15% of female college athletes before Title IX had increased to 44% of college athletes being women and three million more female high schoolers have participated in sports since 1972. Regardless of this progress, future advancements are still to be made.

Making Progress

Dr. Patti Ray (‘65), former Head of Upper School and current School Historian, was a student at St. Mary’s before Title IX was passed. She recalls the importance of this law as a step towards gender equality.

Listen to hear what Ray has to say about her experiences in an all-girls school:

“Title IX was necessary to make sure that doors opened, particularly for females,” said Ray. “I think that level of support from a national federal level was necessary to make sure doors opened.”

Ray played high school basketball in the 1960s, pre-Title IX. She remembers there being a clear difference between high school basketball then and the way it is played now.

“As far as playing sports in the 60s, it was interesting because, at that time, they didn’t open up girls’ basketball to a full court,” said Ray. “They didn’t think girls were able to run the full court.”

Not only were girls limited to half courts, but also specific skills were restricted to certain positions. Guards, like Ray, were limited to guarding while forwards were limited to shooting. At the time, female students rarely had the opportunity to be on a basketball team and were lucky to have one if they did. In the 1960s, the only sports available at St. Mary’s, an all-girls school, were basketball and cheerleading, even without the competition for funding and facilities created by boys’ sports.

Once Title IX was passed, the girls’ basketball team proceeded to use full courts, and the players ceased to be restricted to certain roles. Furthermore, the number of sports available to students grew, starting with the additions of soccer and lacrosse.

Ray’s pre-Title IX experience is only one example of the rapid progress that has occurred over the last 50 years. Not only were high schools progressing towards more equal opportunities within athletics and enrollment, but colleges and universities were also making advancements as well.

Listen to hear Ray recall what it was like being an administrator and advocating for girls’ access to sports:

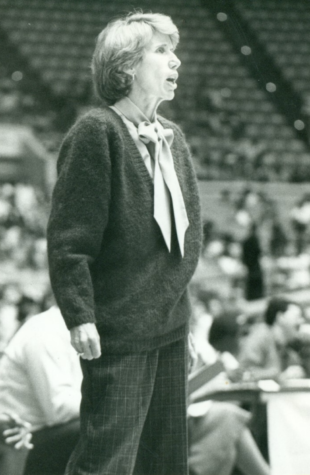

Mary Lou Johns, the former head coach of the University of Memphis women’s basketball team, was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame last year and continues to coach high school sports at St. George’s Independent School. She recalls the recognition that female athletes received after Title IX was passed.

“No one knew that women even played golf or played tennis or played basketball because it was kind of shoved under the rug,” said Johns.

Johns, a pioneer in women’s college basketball, experienced the shift in opportunities for collegiate women’s basketball players when Title IX was enacted.

“If Title IX had not come into effect, I would’ve never been a college coach at Memphis State because there wouldn’t have been a team,”said Johns. “We got where we had more money to spend on uniforms, [and] coaches had more money to recruit and travel. It just gradually started changing.”

Listen to Johns describe the progress of availability to amenities and opportunities for the women’s Memphis Tigers’ basketball team since Title IX was enacted:

Johns’ career as the women’s Memphis Tigers’ basketball coach from 1972 to 1991 showcases 368 victories, making her the fifth-highest winning NCAA Division I head coach in the state of Tennessee women’s basketball history. However, Johns prefers to view her success in a different light.

“I’m hoping I was more successful in directing the lives of the young,” Johns said. “In any sport, coaches are teaching skills, but it is also important to teach other things like life lessons, discipline and being part of a team and an organization.”

Enacted, But Is It Upheld?

Although a wave of progress was sweeping over the country, the transition was not without its challenges.

Mary Murphy, currently the head coach of Hutchison’s high school golf team, remembers an uphill battle for the acceptance of women’s sports when she was playing collegiate golf at Southern Methodist University in the late 70s and early 80s.

“The NCAA [National Collegiate Athletic Association] did not condone women’s sports, support women’s sports or host women’s sports because there was no money in it,” said Murphy. “The president of the NCAA clearly stated that he thought women’s sports were a joke.”

Murphy, who was the number one ranked junior golfer in the country and first team all-American in collegiate women’s sports, received a full athletic scholarship for her four years at Southern Methodist University through the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women.

“That was the only way that the girls got a chance to get their scholarships and play for national championships and all that good stuff because the NCAA refused to even consider hosting women’s sports championships,” said Murphy.

In 1979, Murphy and her team won the National Championship, but the remaining records show otherwise.

“In 1982, the NCAA came in and said, ‘Okay, we’re going to do women’s sports now, now that you’ve done all the work, we’re going to take this over,’” said Murphy.

The NCAA not only began to administer athletic scholarships for women, but they also forced universities to choose the NCAA over AIAW, threatening to no longer sanction schools that associate their women’s athletics with the AIAW.

In 1981, the AIAW unsuccessfully sued the NCAA for “unlawfully using its monopoly power in men’s college sports to facilitate its entry into women’s college sports and to force the AIAW out of existence.” The AIAW ceased to exist on June 30, 1983 and along with it, most of its records.

“The NCAA doesn’t even recognize our records, and that’s getting ready to change. They don’t have me in as as a national championship winner,” said Murphy.

For Murphy and her teammates, their National Championship rings are the only remaining proof of their victory in 1979.

“It’s like it never happened. They can pretend all they want that it didn’t happen, but of course it did. According to the NCAA, Mary Murphy didn’t play collegiate golf, nor did she win a national championship,” said Murphy.

Where We Are Today

Today, Title IX’s impact reaches athletes of all levels, from intermediate players to those aspiring to play professionally.

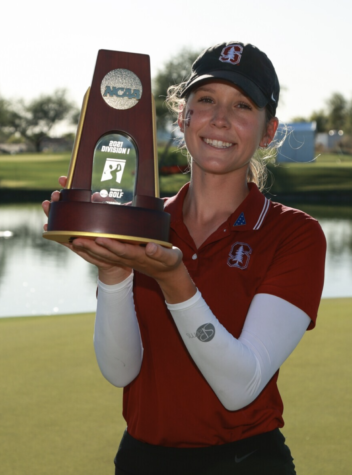

Memphian Rachel Heck is an athlete who has received spotlight recognition for her achievements as a collegiate golfer at Stanford University. The junior is ranked fourth on the World Amateur Golf Rankings.

“I started playing golf just as a fun activity that my sisters and dad and I could do together,” Heck wrote in response to my questions. “At the time we didn’t know about tournaments and college scholarships or any of that. Once we learned about Title IX and the potential for athletic scholarships, it provided even more motivation to keep working on my game.”

Heck is not only grateful for her opportunity to compete at the collegiate level because of Title IX, but also is thankful for the bonds and memories she has created as well.

“My freshman year, I won the individual NCAA championship,” she wrote. “But the best memories have been when I’ve been a part of a special team. Nothing compares to the feeling of having teammates, practicing together, and playing for each other. No individual success will ever mean more than [that].”

Heck’s position on the Cardinals’ golf team is highly decorated with awards and championships, including the 2022 NCAA Women’s Golf National Championship, the Annika Award and 2021 NCAA Women’s Golf Individual National Champion.

Heck’s high school golf coach at St. Agnes Academy, Cynthia Giannini, is a highly recognized coach with 18 regional championships and six state golf titles. She recognizes the opportunities her own golfers have had due to Title IX.

“Title IX has opened the door for not only female athletes at Rachel Heck’s level but for all levels,” she said. “Rachel has been able to attend her dream school, Stanford University, to pursue academics and play golf for the top school in the country. At Stanford she was also able to join the Air Force ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) program due to Title IX being passed.”

It is easy to assume that with trailblazers like Johns, Murphy, Giannini and Heck, Title IX’s work is complete. But there are still startling inequalities in school sports for women.

“It’s still nowhere equal, and I don’t know if it ever will be totally equal. It is better, but there’s still a lot that can be done,” Johns said.

Murphy agrees.

“Maybe it [the fiftieth year anniversary of Title IX] will enlighten some female athletes to not sit back and not speak up when you don’t think things are fair and you’re not being treated equally. It’s important that women and girls keep fighting to make everything equal, as equal as can be. And to give young girls an opportunity to chase their dreams.”

— Mary Lou Johns

“Coach Johns was right when she said, ‘Don’t forget about it [Title IX].’ She’s still fighting the fight, and it’s pretty incredible,” said Murphy.

She’s not the only one. Today, Murphy and her teammates from SMU are working towards bringing their collegiate accomplishments the recognition they deserve. They are gathering records by searching through old newspaper microfilms and personal scrapbooks, and so far, they have collected 10 years of concealed history, like the 1979 National Championship.

Sex discrimination in school sports is not just a thing of the past. Female high school water polo players in Hawaii are currently pursuing a discrimination case using Title IX. Female athletes were expected to practice water polo in the ocean and change into their uniforms at the local Burger King, while the male athletes practiced in pools and were provided their own locker rooms by the high school.

Next year at 5:00 AM, you will likely still find Ciaramitaro practicing her breaststroke in a pool, but then the swimmer will be practicing in the facilities of her dream college, Vanderbilt University.

Ciaramitaro was able to achieve her dream of attending a Division One college with an athletic scholarship after countless hours of practice and diligence.

A dream that would not have been possible without Title IX.

This is sophomore Hana Barber’s first year on Tatler. During her free time, Hana loves to perfect her skills on the piano and on the golf...

This is senior Charlie LaMountain's fourth year on Tatler. While Charlie is one of Tatler's artists, she is also known for rock-climbing. A midtown-lover...