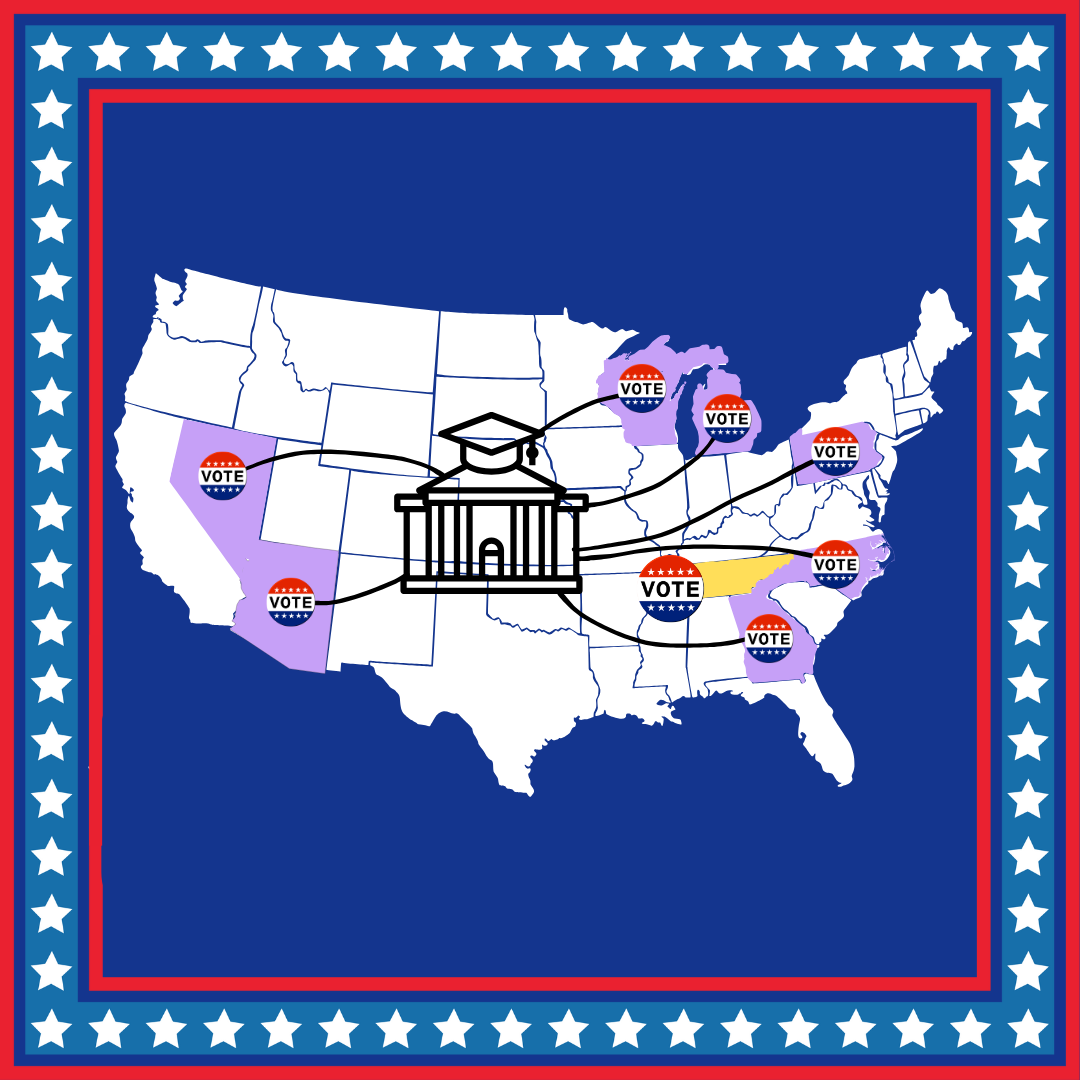

“What colleges want is a diverse student body, and diverse in every way possible,” St. Mary’s college counselor Beverly Brooks said. “They want geographic diversity, they want socioeconomic diversity, they want racial diversity, gender diversity [and] religious diversity.”

But now schools have one less tool to find it.

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions. Most U.S. colleges and universities can no longer consider race when selecting new applicants.

“Checking a box for race was never a requirement, but it was always an option,” Brooks wrote in an email. “It remains optional now, though many colleges are choosing to remove it when they download a student’s application, the same way they might choose not to look at a student’s essay, social security number, or some other information provided.”

The Supreme Court’s decision, which upended the practice of affirmative action, applied to two concurring lawsuits, Students For Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. the University of North Carolina (UNC) and SFFA v. Harvard.

The plaintiff, SFFA, filed the lawsuits in 2014. It argued that Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programs should be race-blind. SFFA is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to omit “racial classifications and preferences” from college admissions. It has more than 20,000 members. On its website, SFFA argued that “a student’s race and ethnicity should not be factors that either harm or help that student to gain admission to a competitive university.”

Their argument hinged on evidence that Asian students may have been held to a different standard than other groups in college admissions. According to the court’s published syllabus of the cases, SFFA argued that “over 80% of all black applicants in the top academic decile were admitted to UNC, while under 70% of white and Asian applicants in that decile were admitted.”

A St. Mary’s alum from the class of 2022 (who wished to remain anonymous given the controversy surrounding affirmative action) said that even though affirmative action was created with good intentions, it had drawbacks that the Supreme Court cases highlighted.

“I do think affirmative action has done a lot to close those [racial] gaps [in admissions],” she said, “but I also think it’s harmed other minorities in the process. For example, like me specifically, I’m South Asian, and I know that there has been a lot of scandal around colleges holding higher standards for specifically Asian students, and that includes East Asian, South Asian,pretty much just if you put Asian for your race, then you’re automatically held to a higher standard, and I feel like I did notice that comparing myself to my white friends. I knew that I had done all the same things that they did, yet a lot of them still got opportunities that I didn’t.”

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of SFFA, saying that affirmative action violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

In his concurring opinion, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programs… cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause.”

He added, “Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin.”

Affirmative action policies placed an emphasis on race with the goal of ensuring that the demographic of a company, school or institution reflected the demographic of the population at large. They were meant to provide equal opportunities for historically marginalized groups, including women and minorities.

They also have decades of legal precedent.

The term “affirmative action” first appeared in an executive order issued by President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Executive Order 10925 instructed federal contractors to take “affirmative action to ensure that [job] applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.”

Three years later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 established a broader set of protections, outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued an executive order requiring government contractors to take “affirmative action” to expand job opportunities for minorities.

In the 1978 case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court upheld affirmative action in college admissions for the first time, on the condition that colleges cannot admit applicants based on race alone, nor can they use racial quotas by setting aside a certain number of spots for minority students.

For over 40 years, affirmative action was a staple part of college admissions at many schools. The period of affirmative action corresponded with a period of increasing diversity in college admissions. According to the Clinton White House Archives, in 1965, just 4.9% of college students nationwide were Black. Once affirmative action was introduced, that number grew steadily each decade. By 1990, it had increased to 11.3%, and, according to the Postsecondary National Policy Institute, it had reached 12.5% by 2020. The United States Census Bureau states that currently, the U.S. population is 13.6% Black.

But the history of affirmative action also includes controversies and legal challenges.

Affirmative action in education was challenged at the Supreme Court in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) and Fisher v. University of Texas (2013), but it was upheld both times.

Recent changes in the political makeup of the court may explain the new ruling. The Supreme Court consists of nine justices and votes on a majority-rules basis. Currently, there are six conservative-leaning justices and three liberal-leaning justices serving on the court.

Former president Donald Trump appointed the three conservative-leaning justices — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barret — during his term, shifting the court’s overarching political view to the right.

It ruled against affirmative action 6-3 in the case against UNC and 6-2 in the case against Harvard, splitting across ideological lines both times. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson abstained from voting in the Harvard case because she had served on the school’s advisory board.

In her dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who is liberal, wrote, “The majority’s vision of race neutrality will entrench racial segregation in higher education because racial inequality will persist so long as it is ignored.”

Kate Stukenborg (‘20) wonders why affirmative action has been disputed so much more than other programs meant to increase diversity.

“I’ve wondered why [affirmative action is] so controversial while tools like DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] director positions, updated curriculum or the gradual elimination of requiring standardized test scores are decided on with more agreement,” she wrote in an email.

Stukenborg believes that affirmative action was a good thing that some misunderstood.

“It seems like the perspective of some white students and parents is that they deserve a spot at a school, and that spot is being ‘taken’ by someone less deserving,” she wrote. “What I would say to this is that a) the diversity that student adds is valuable in itself and is reason enough to consider them more thoughtfully as a potential student, and b) affirmative action doesn’t work by ‘taking’ but by allocating resources according to need. It’s ‘affirmative’ because it affirms the varying levels of need among students as well as the value of students who historically have been undervalued.”

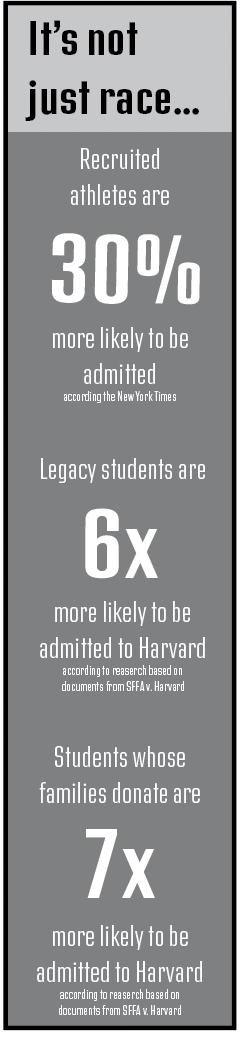

According to Brooks, there are a host of other factors giving certain students an advantage in college admissions.

“Race isn’t the consideration that I think we should be as mindful of as things like legacy status or recruited athletes or students whose families have given significant amounts of money to the school,” Brooks said.

According to ABC News, between 2014 and 2019, a student applying to Harvard was about six times more likely to gain admission if they were a legacy student and about seven times more likely to gain admission if their family made a donation to the school. According to The New York Times, recruited athletes also have a significant advantage in the admissions processes at 19 elite colleges. Specifically, recruited athletes have a 30% higher chance of acceptance to these schools than non-athletes.

Brooks recalled a situation at a previous job where a student was accepted to Duke University, a highly competitive school, in spite of having low standardized test scores because he was a recruited athlete.

“He was a D1 soccer recruit,” she said. “He ended up staying for a semester and then signing a professional contract, but he had like an 1150 on the SAT, certainly not the standard that most students have when attending Duke, but because he was an athlete, he got in.”

Ashley Graflund (‘21) is a 2nd class cadet at the United States Air Force Academy, one of the few schools exempt from the affirmative action decision. Because her school is just 30% female, she thinks that affirmative action might have helped her gain admission there.

“I could definitely be considered as a diversity admission,” Graflund wrote in an email. “I would be remiss if I believed my gender did not have an impact on my admission.”

Even though she suspects affirmative action probably aided her in her college search, she sees both potential pros and cons to it.

“I believe that diversity of upbringing, culture and mind are important aspects of having a well-rounded education,” she wrote. “However, [affirmative action] can mean that well-deserving students who may not be as diverse on paper are overlooked in the admissions process.”

(Graflund added that she is not representing the views of the United States Air Force or the Department of Defense and that these are her personal opinions.)

Although she said she can sympathize with both sides of the controversy, current senior Zoe McMullen sees affirmative action as a vital resource for first-generation college students and for students from low-income households who may not have access to the same resources as students from high-income households.

“Affirmative action really helps equal the playing field for those students,” she said. “Honestly, bring back affirmative action.”

Despite its broad impact, it is not easy to determine how affirmative action affected any individual’s college search in the past, according to Brooks.

“I don’t know that it made it easier or harder, especially at highly selective schools, because the reality is that colleges accept students who can do the work, and so I think there’s this misconception about affirmative action that students who are somehow incapable of doing the work are the ones getting in,” she said. “What’s important to know is that race especially is not the only thing considered when a student is applying to college, and so I don’t know that it would positively or negatively affect past applicants from St. Mary’s.”

Nonetheless for Brooks, the end of affirmative action feels like a net loss.

“I think affirmative action was a good thing,” she said. “I think we should always be looking for classrooms that have diverse voices, and that create space and opportunity for students who wouldn’t have had that opportunity otherwise.”

Of course, applicants still have the opportunity to share their unique stories and talk about their race, culture and background. Because affirmative action has ended, some colleges have created new essay prompts that allow students to explain their identity and their role in their community.

“If there’s a part of their background that they feel is central to who they are, there are spaces where they can share that,” Brooks said. “It’s important to know that students should always be sharing their story authentically.”

![[GALLERY] Walking in (Downtown) Memphis](https://stmarystatler.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E1DAD3FE-E2CE-486F-8D1D-33D687B1613F_1_105_c.jpeg)