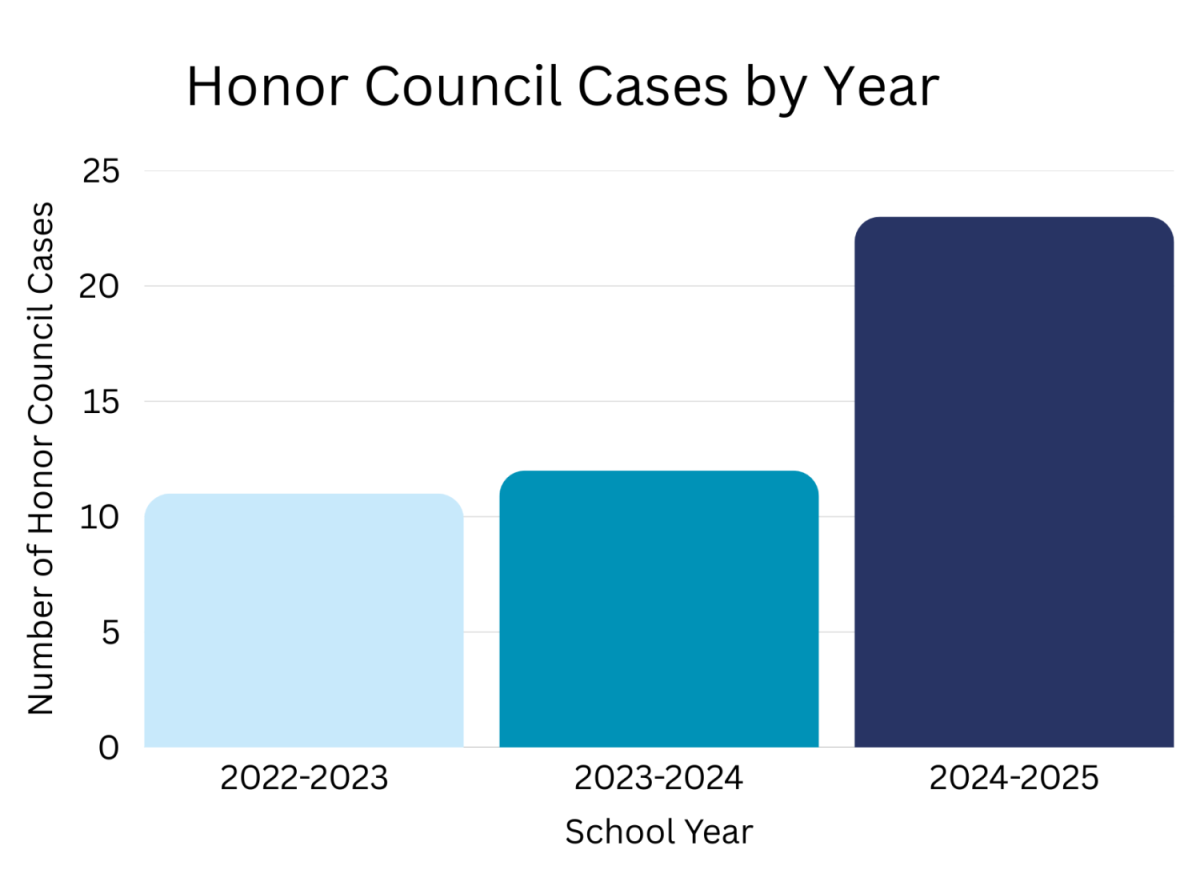

For the last weeks and months of her senior year, Honor Council President Claudia Ribeiro was busy. Very busy. So far this year, the Honor Council has reviewed 23 cases, a jump from recent years. During the 2022-23 school year, there were 11 cases, and in 2023-24 there were 12.

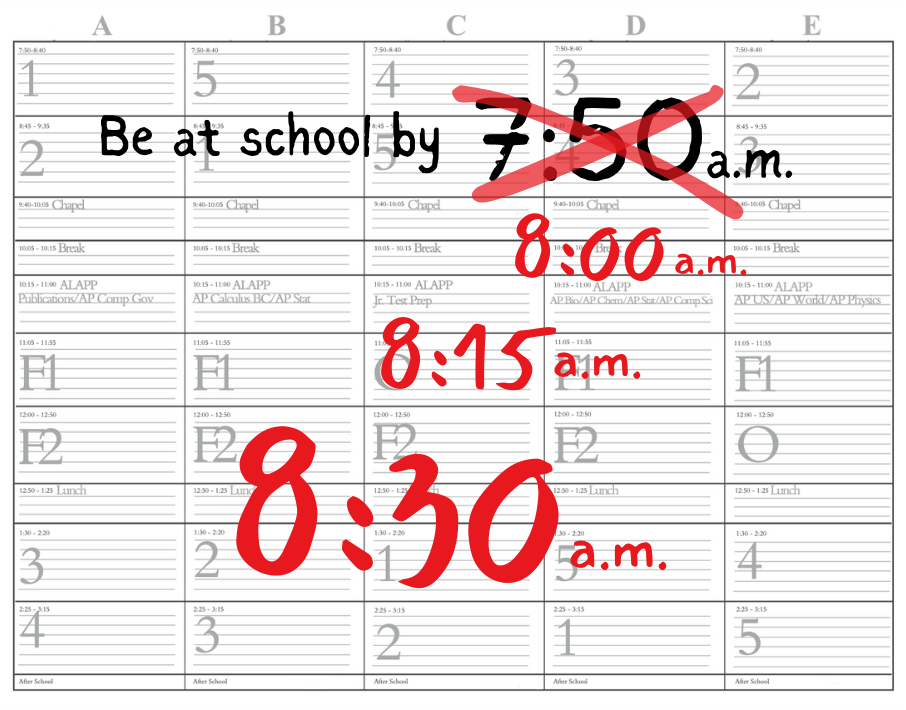

“Recently, we have been meeting, if not once, two to three times a week, which means that if we are crunched for time, I will be interviewing anywhere from two to five people in a day, and we will be covering, not necessarily five cases, but five people, some of whom might be related to one case,” Ribeiro said.

The case load for the Honor Council at St. Mary’s has increased during the 2024-2025 school year due to the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), such as ChatGPT. AI usage has been detected most often in essays or other writing assignments and the Honor Council has to figure out whether or not they can trust these results.

Ribeiro is not the only one that has felt the effects of this increase. Lucy Lyon, one of the honor council sophomore representatives, has noticed recently that the Honor Council as a whole has met together more often.

“It’s pretty spontaneous, but I guess it just depends on how many people are cheating or violating the honor code,” Lyon said. “I think we have one every two weeks for this semester at least.”

Lyon explained how the growth in AI usage affected the ways they handled cases this year.

“We’re seeing a lot of AI cases, just either fully generated, like essays, or just 35% AI in this section, and we have to kind of figure out if it is AI or not,” Lyon said.

What to Expect If You’re Suspected

The Honor Council process typically starts off this way, with Ribeiro conducting interviews for cases before the entire council reviews them.

“Either a teacher or student will report or will tell me that they have something to report,” Ribeiro said. “I will then interview whoever is doing the reporting, whether that’s a teacher or student, during usually ALAPP, and they will tell me briefly what happened with the student and just a little bit about the potential violation as a whole.”

The Honor Council sponsors, upper school biology teacher Courtney Gillespie and Spanish teacher Sarah Kerst, ask the accused student to explain their version of the incident during an interview with Ribeiro.

“During the interview everything is very non-accusatory,” Ribeiro said. “We’re not trying to be very harsh. It’s all very general questions. We just want the student’s side of the story so that when we get to the meeting as a council, we can give both sides everything.”

The Honor Council then meets to hear about the overall story of the case without the student present and makes a decision they all agree upon.

“I’ll finish interviewing the student, and then that day, during lunch, we’ll meet as a council,” Ribeiro said. “Everything is anonymous, so I will ask for a fake name for the student, and I will give the overview of both what the reporter said and what the student said, and then we will vote until we have reached a unanimous decision, whether that’s that the student is innocent, negligent or guilty.”

What it’s like

Because of the secrecy of the process and the anonymity used for any student who is accused, it’s difficult to find students who are willing to share their own experiences with the Honor Council. But through the Honor Council sponsors, Tatler was able to get two students to write anonymously about their experience.

“[The process was] decently quick and somewhat concerning just because I didn’t really know what to expect,” one student wrote.

That student wished the council had given them advance notice that they were going to be questioned.

“[I] just would’ve liked more warning on what was happening because I didn’t know I was being called to the Honor Council until I sat down in that room,” the student wrote.

The lack of warning is deliberate. Gillespie explained that they purposely don’t give warnings in order to prevent stress and overthinking before the student meets with the Honor Council.

In the past, students were given a heads-up about the meeting but were often unable to sleep or focus during classes, causing the Honor Council to rethink this part of the process.

“We really just kind of call them in to start the conversation, instead of giving them a ton of advanced notice and stress,” Gillespie said.

If the student was suspected but it turns out there was an innocent explanation, the matter gets resolved without any further action.

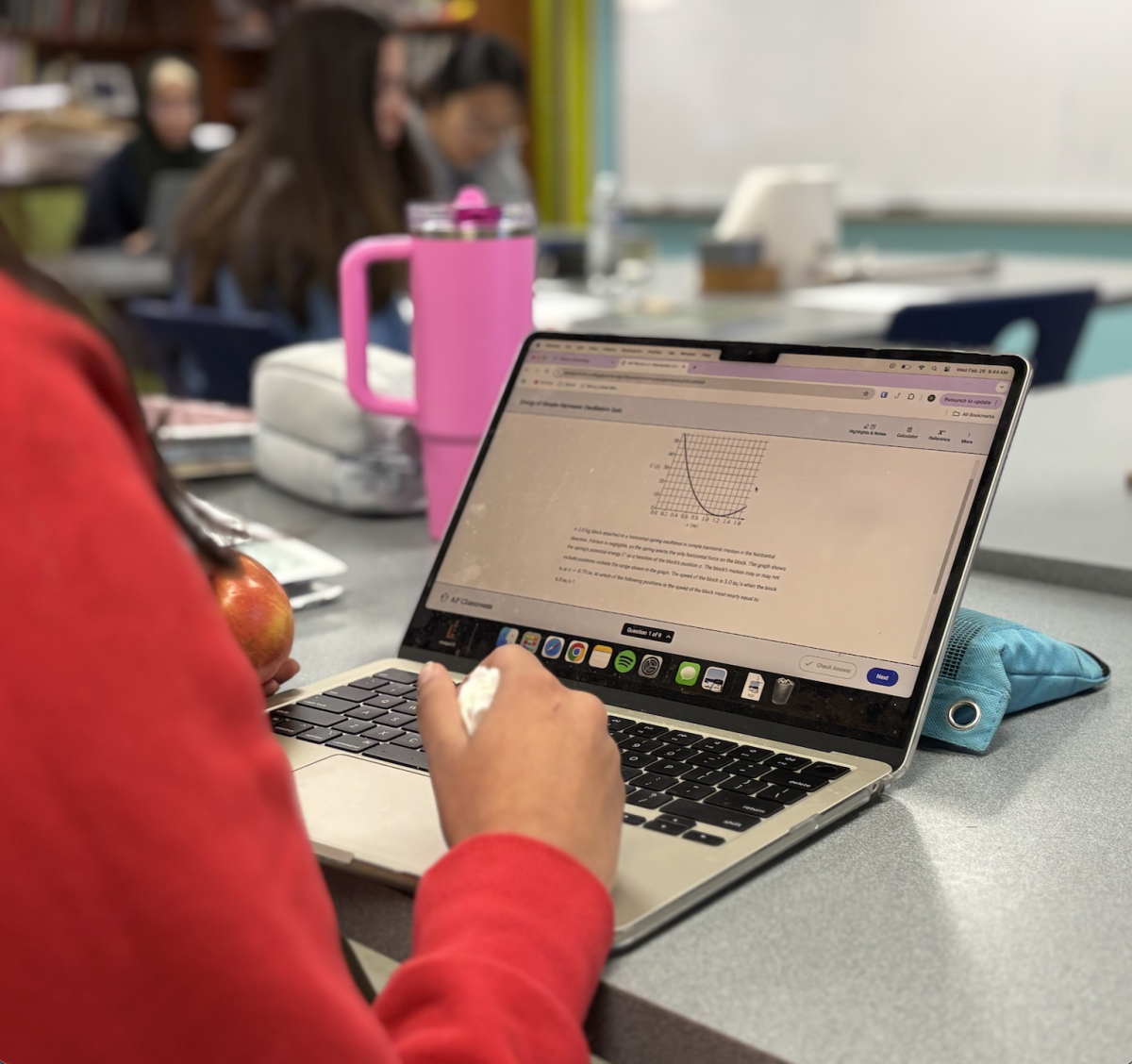

“If there’s something in their essay that shows that they copied and pasted a big chunk and we might suspect that it was AI, but if they can show us the second document that they were working on, they can clear it up in that moment rather than going to the Honor Council,” Gillespie said.

While copying and pasting is not by itself a violation of the honor code, there are times when this is a sign that a student plagiarized or used AI, prompting the Honor Council to have a conversation with that student about where they got their work from.

Another part of the Honor Council that stood out to a student was how involved students were in the process.

“The people involved with it just kind of surprised me in a way,” the student wrote. “I didn’t expect to be in the room with a student.”

Why have an Honor Council?

Other schools have honor councils that are not as student-focused as St. Mary’s and have more teacher involvement. However, Ribeiro believes that there are a lot of positives when students are the ones leading the honor council.

“It has really meant a lot for me to be able to step into this role and see the Honor Council talk and discuss without any judgment,” Ribeiro said. “I have learned a lot of invaluable skills from being able to be the president of the council.”

Because the council reviews students’ experiences with the honor code, Kerst believes it’s important that other students can voice their views on the matter.

“Because as teachers, we could be like, well, it’s not that hard. Life is not that stressful,” Kerst said. “Having that firsthand experience with students, I think, is really important.”

While the students on the Honor Council have been dealing with a larger load of cases this school year, Gillespie thinks the council might start seeing changes after students receive consequences for infractions.

“When they’re found guilty, the Honor Council votes on consequences, and it’s usually writing some sort of reflection, maybe apologizing to the teacher, and then a grade reduction, which is usually based on the teacher’s discretion,” Gillespie said. “The first [time being] guilty results in them being ineligible for running for a four-point office for the next calendar year.”

Gillespie expressed hopes that they’ll even see a decrease in the caseload if students begin choosing alternatives to using AI.

“I think the number of AI cases this semester has been pretty unusual, and I’m hoping that the rate goes down,” Gillespie said. “We have multiple ways to detect it, and it’s not worth it. It’s better just to put in the work. Or if you know you can’t get the work done on time, ask for an extension instead of getting a zero for using AI, and get a little reduction for turning it in late.”

![[GALLERY] Walking in (Downtown) Memphis](https://stmarystatler.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E1DAD3FE-E2CE-486F-8D1D-33D687B1613F_1_105_c.jpeg)