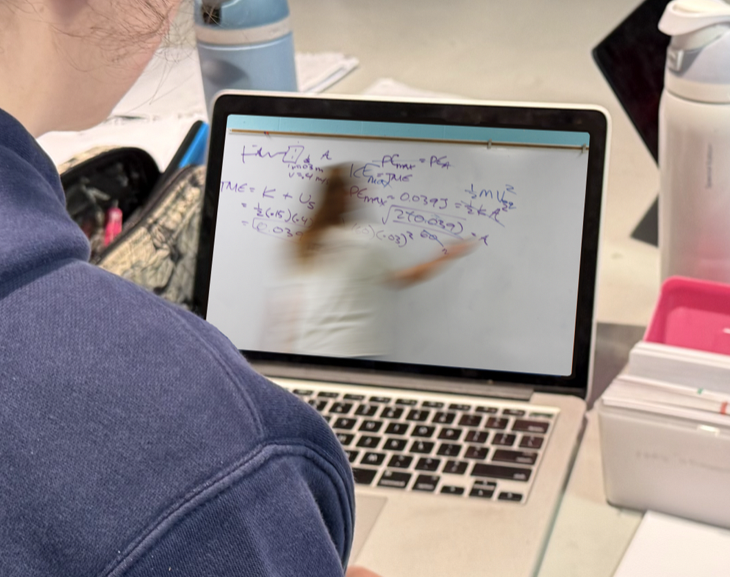

For many St. Mary’s students, there is an extra step before hitting play on a video. The cursor moves to the playback speed button followed by an increase to 1.25x, 1.5x or even a full 2x speed.

But is there a price to pay for all this speed?

Saving time

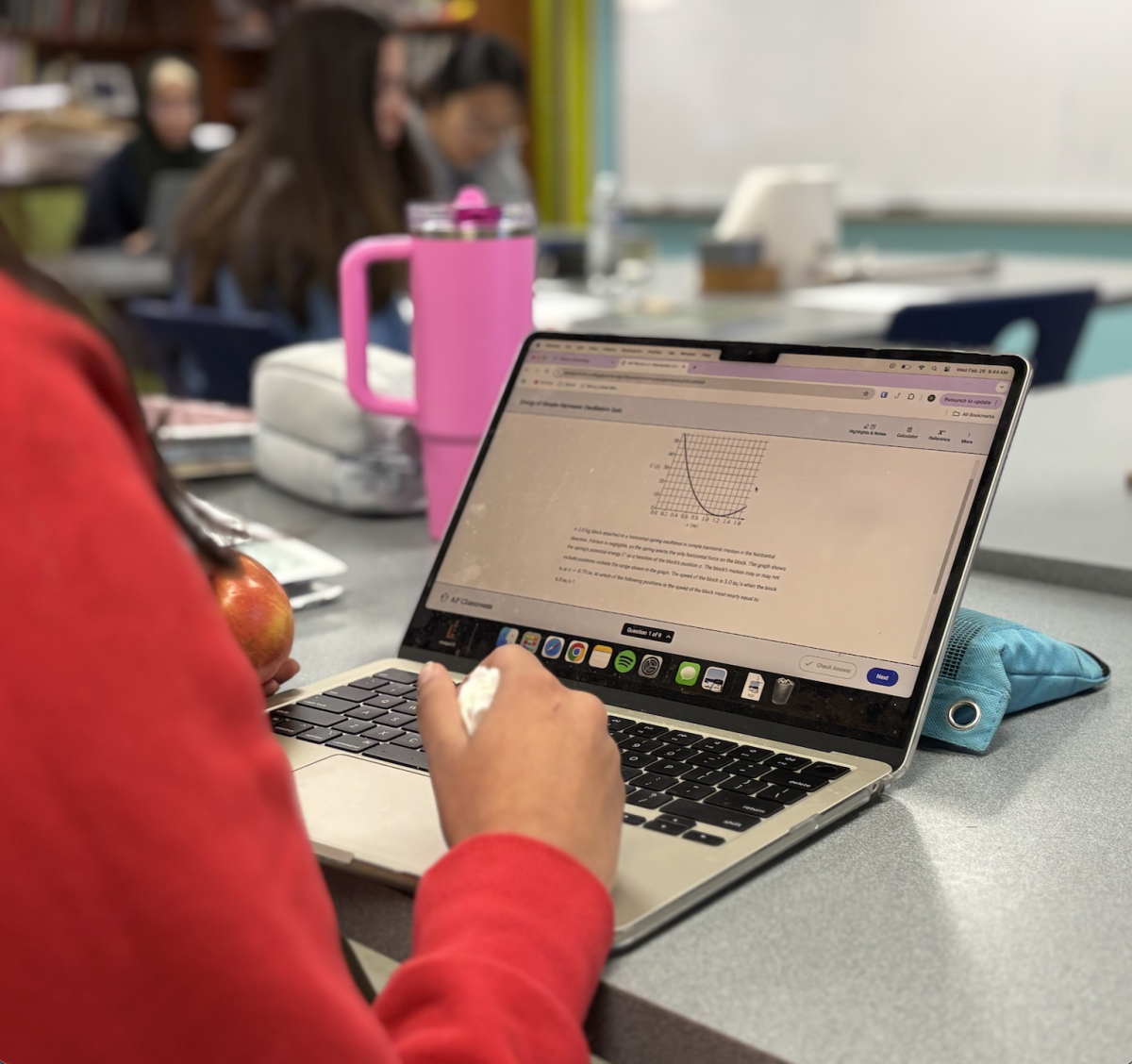

Sophomore Lauren Ehrhart speeds up videos for class to save time and even finds it helpful for understanding the content.

“I speed [assigned videos] up because, personally, I lose track of what I’m learning if what I’m being told is too slow. I’ll get lost in the words,” she said. “If it’s sped up to a more talking pace, I can understand it better.”

Ehrhart’s habits reflect those of the majority of St. Mary’s students. According to a survey Tatler conducted, 97.6% of students also speed up videos for school.

For Ehrhart, the faster pace not only keeps her attention in check, but also helps her manage her time both during and outside of school.

“I think we just want to get the work done,” she said. “So if the video is faster, then it takes [fewer] seconds to get the work done.”

The desire to get done in a hurry also drives students to speed up other media. About 58.5% of students surveyed said they also speed up audiobooks to complete school reading. Junior Audrey Stifter is one of those students.

“I usually speed up audiobooks, because usually the audiobook people talk slow,” she said. “I just get impatient with how slow some of them go, so I’ll just speed it up. Or sometimes if it’s so slow, I just focus on how slow it is, and I’m not listening to it.”

Teaching in the new normal

For English department chair Shari Ray, increasing the speed of audiobooks is unhelpful for her own understanding, but she doesn’t mind her students choosing to do so for the sake of productivity.

“I, myself, as a reader, prefer to read the words on the page, take my time, and annotate and mark and dog[ear] your pages,” she said. “But I also understand that students have a lot going on.”

Down the hall in her physics classroom, Margaret Huber doesn’t have a problem with her students increasing the speed of the videos she assigns. In fact, Huber even speeds up videos herself.

“I don’t think for physics, [higher speed] changes anything as long as you are able to absorb the content,” Huber said. “I think, for me, the AP [Physics] videos talk too slowly, so I need to speed it up.”

But Rainey Segars, chaplain and upper school religion teacher, wonders if something isn’t lost when students speed up the content. For a long time, she did not approve of her students watching her videos at 2x speed. She worried that speeding up material might result in a loss of understanding of the information.

“If I’m with this content for 3 minutes rather than 10 or 15, did I process it the same?” she said. “I struggle to believe that, and I wonder if learning is as deep [when sped up].”

Despite this, she eventually conceded, allowing her students to watch at a quicker pace.

“[My students] claim, and they have told me and convinced me, that actually they do understand things better when it’s moving more quickly because that’s what they’re used to,” she said. “But that’s not how I grew up watching things.”

Her students may have a point. A 2022 UCLA study revealed that UCLA undergraduates watching videos at speeds up to 2x the original speed did about the same on multiple-choice question assessments as those watching them at their recorded speeds. However, students watching the videos at 2.5x speed did poorly on the assessments.

“Students can save time and learn more efficiently by watching prerecorded lectures at faster speeds if they use the time saved for additional studying, but they shouldn’t exceed double the normal playback speed,” Dillon Murphy, a doctoral student in psychology at UCLA, wrote.

Stifter knows about those limits firsthand.

“I feel like it’s probably not the best for me if it’s going super fast,” she said. “I don’t think that it would do me good to speed up videos I’m supposed to be taking notes on because sometimes I’m not paying attention when it speeds up so much.”

What’s the rush?

Following her students’ lead, even Segars has started to speed up some content, but only for videos she has little interest in.

“Because of the girls, I have just in the last year started to play things on 1.25[x speed],” she said. “So it’s like the one click, and that’s fast enough.”

But she said that she still cannot shake the feeling that while shifting to quicker speeds and shorter attention spans, we are leaving behind some of our best skills.

“I fear we are raising a generation of people who do not tolerate boredom and therefore don’t display the creativity and the self-regulation that being bored gives you. And it’s spidering out, it’s making us shorter-tempered, it’s making us more demanding,” she said.

According to a study conducted by Dr. Gloria Mark, a psychologist at the University of California Irvine, the average attention span on a screen went from 75 seconds in 2012 to 47 seconds in the last few years.

“[Forty seven seconds] seems to be the new normal because we seem to have reached a steady state over the last 5 or 6 years,” she wrote in her study. “I would argue [this change is] not a good thing.”

Noticing the effects of this change in herself, Ehrhart realizes how she has acclimated to a new normal in terms of speed.

“I feel like it’s just habit to speed up everything, right? Even if it doesn’t need to be sped up,” she said. “And then after a bit of the video, I’ll realize, ‘oh wait, it doesn’t need to be sped up.’”

![[GALLERY] Walking in (Downtown) Memphis](https://stmarystatler.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E1DAD3FE-E2CE-486F-8D1D-33D687B1613F_1_105_c.jpeg)