The familiar chiming and ringing of phones will echo the upper school halls for the last time as this school year comes to a close.

On Feb. 13, Head of School Albert Throckmorton announced a new phone policy for the high school. While the logistics of the enforcement of the policy are yet to be determined, the new near-total cellphone ban met with plenty of controversy among students, faculty and even alumni over the past month since its announcement.

Initial reactions from many students were negative.

“I think it’s actually just gonna create more drama,” freshman Eliza Frazer said. “People who actually need their phones in class or who need their phone for a project are just gonna be annoyed, and it’s not going to work out.”

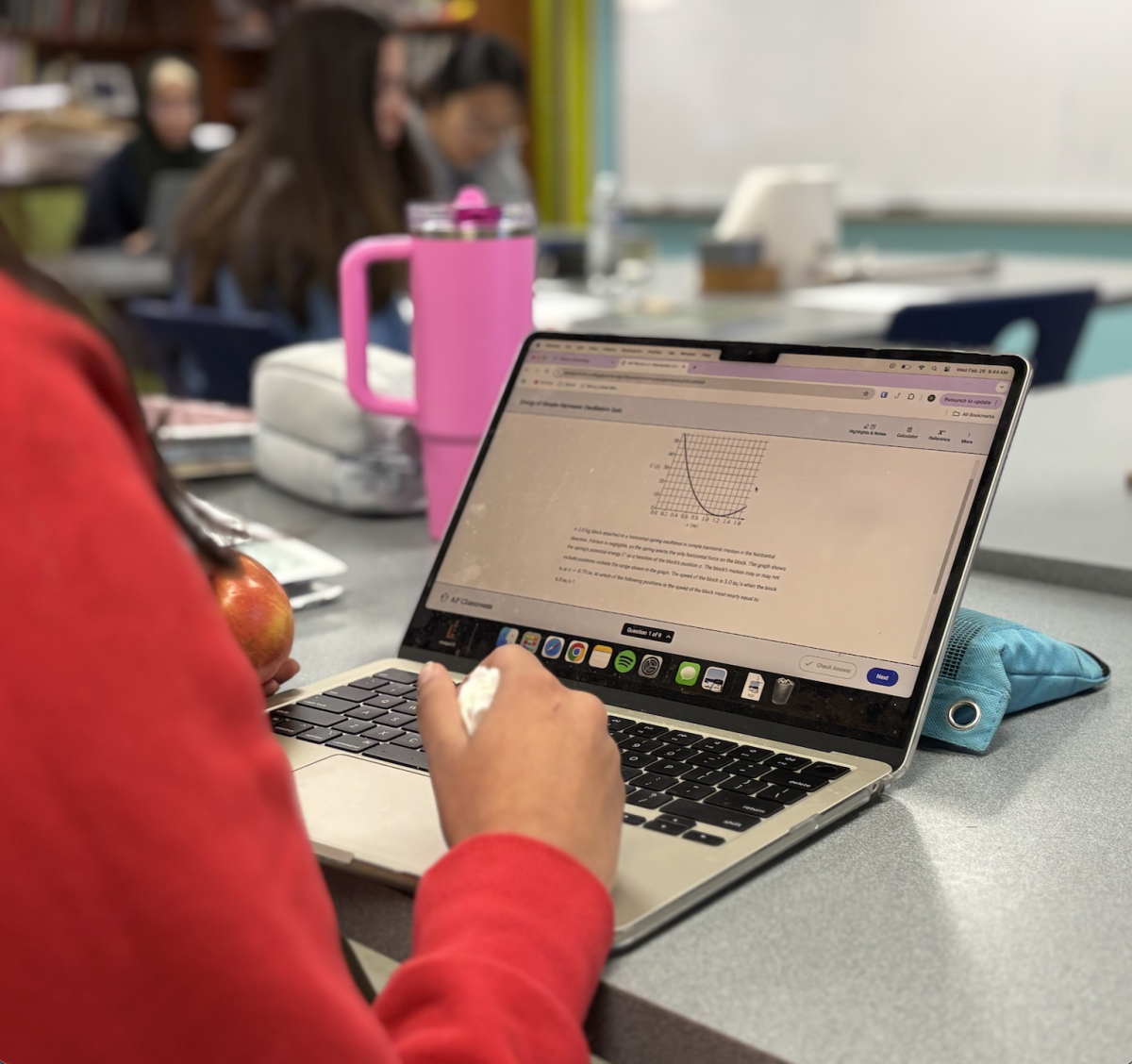

Junior Ivy Carls, who uses her phone for planning her school day and checking her classes online, said she felt there were a lot of legitimate reasons for students to have their phones during the day.

“I use it for planning and my Notes app, [and] my calendar is on my phone,” Carls said. “I text friends asking about homework and stuff, and it’s just gonna be harder to get that information if I only have a computer.”

Students also rely on their phones for contact with their family, making the phone ban inconvenient for students like sophomore Molly Ginn.

“I text my boyfriend or my grandma,” Ginn said. “Just basically needing to get into contact, it’s just gonna be really annoying.”

Freshman Ellie Kate Edwards pointed out that laptops, a requirement for all high school students at St. Mary’s, have most of the same functions as a phone, including potentially distracting social media.

“Snapchat is online, Instagram is online [and] you just go on TikTok on your laptop,” Edwards said. “So if they’re worried about productivity, we could still do that.”

Despite student concerns, schools across the country have already implemented restrictive phone policies.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports that over 77% of public schools have policies prohibiting students from having their phone during class. Thirty-eight percent of public schools prohibit phone use during free periods, meal times and extracurricular activities. Fourteen states have passed laws in K-12 classrooms on cell phone usage, but only eight states have implemented policies and executive orders that ban or limit cell phones in classrooms.

St. Mary’s alum Shea Quraishi (‘04), who is now an educator specializing in helping teachers support children’s social and emotional well being, believes a new phone policy is needed.

“Research has shown us for years that children and teens who spend too much time on screens and on social media are less able to self regulate,” she said. “They are less able to read facial expressions. They are more prone to anxiety and depression. They’re less able to focus their attention for long periods of time.”

According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), studies have found a link between mobile phone use and adverse effects on brain activity, reaction time and sleep patterns.

But enforcing the new phone policy raises a different set of questions.

In years past, the high school has left phone restriction to the teachers, giving them phone boxes. Teachers may instruct students to place their phones in a box placed out of reach, either at the beginning of class or as they see fit.

A year ago, the middle school moved to using phone lockers. Students are required to place their phones on a locked shelf in the morning and only allowed to collect them at the end of the day.

Phone lockers are a possibility for the high school next year, too, as are cell phone pouches like those from Yondr. With the pouches, at the beginning of the school day, students would be required to place their phone in an individual bag that is locked using a magnet. Students would only be able to unlock the bags using the same magnet at the end of the day.

Carls said she thinks loopholes in the policy may ensure its failure.

“How are you gonna know that people are actually putting their phones into the little bags?” she said. “How do you know that that’s their actual phone and not just like an extra phone from 2011?”

But in the Middle School, enforcement of the phone lockers has been surprisingly smooth. According to Head of Middle School Katherine House, reception of the policy was much less negative than expected.

“Students don’t seem to be complaining,” she said. “I’m sure they have, but I just I feel a little bit more peaceful.”

Eighth-grader Lucy Moore agreed.

“I think it’s worked pretty well to keep people from using their phones in between class,” she said. “I think a lot of people without the urge to go grab their phone are staying in their home rooms more and completing work.”

For eighth-grader Mia Gandy, however, the inability to access her phone publicizes preferably personal conversations with parents.

“Sometimes, there’s something I need to text my mom about it’s not something I want to go into the office and call and say with everybody listening,” Gandy said.

But House said she sees a significant upside. Phone lockers have decreased the number of students breaking the rules around phones and getting themselves in trouble.

“I’m not constantly hearing that a student’s been caught in their locker on their phone, which last year, it was just constant,” House said. “[In the past], they couldn’t go to the bathroom without checking their phone, which was against the rules. That then put them in a bad position.”

Sophomore Carmen McGhee said she hopes the ban may be similarly successful in the high school, encouraging students to be more responsible with the use of their free time.

“I feel like a lot of people use their time on their phone when they shouldn’t be,” McGhee said. “Then they get mad around the teachers because they’re underprepared for a test or something, and it’s really just like they’re not using their time wisely.”

McGhee also hopes that the policy could help friends work through conflict in a healthier manner. When students don’t have access to their phones, they aren’t able to distract themselves when something needs to be resolved.

“It’ll make people actually have a stronger connection with their friends, and when a conflict does happen I feel like it only makes people talk,” she says. “It’s worse when they have their phone [because] they can ignore it.”

Sophomore Abigail Brown said she believes the policy won’t be that drastic a change and may even have positive effects on the school environment.

“It doesn’t really impact me that much. If anything, it would be kind of nice to have that disconnect.” Brown said. “I don’t think it’ll be as bad as everyone is thinking it will be.”

Teachers generally seem to hold positive attitudes towards the policy.

Sarah Kerst, Spanish teacher and Honor Council sponsor, said she believes a policy has the potential to improve both students’ and teachers’ experiences.

“I think it’s gonna do wonders for mental health around the school,” she said. “I think it’ll do wonders for productivity and actual relationship building with each other when you don’t have your phone.”

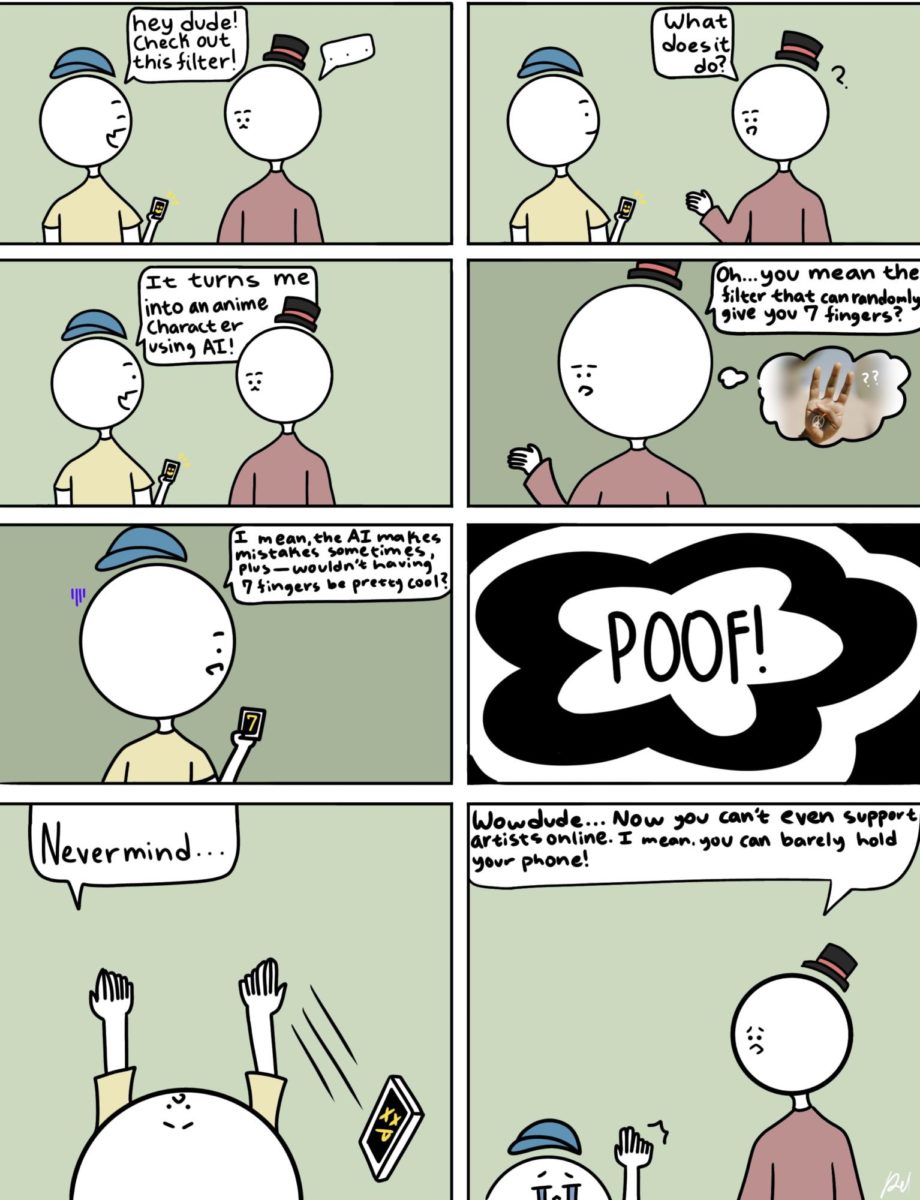

Kerst also thinks restricting phones will limit the accessibility of AI for use on assignments and therefore reduce the number of AI-related cases being sent to the Honor Council.

“We are finding right now that there’s too much temptation,” she said. “Kids are busy. Kids are stressed. Hopefully, this will help take away that temptation. Phones are a distraction and maybe it will be helpful in the day-to-day to have more time in class without distractions to actually get that work done.”

For alum Ashley Graflund (‘21), any potential positives are outweighed by her concerns about safety.

Graflund said she worries that if students are unable to use their phones, parents and students will not be able to receive critical information during emergencies. She remembers an experience when she was a student and phones were essential during a school lockdown.

“It was a situation where no one really knew what was going on. We just knew we were in a lockdown,” she said.“I was the only one in the class with my phone on me, and I was passing my phone around to other girls for them to reach out to their parents because no one knew what was happening… It’s a safety issue. I would not have wanted to be there without a phone completely.”

Quraishi, who teaches younger children at an independent PreK-12 school and has two young children of her own, worries about a different kind of safety.

“We’re putting phones, tablets and smart watches into the mix at a stage in life when girls are developing a sense of themselves and an understanding of the world, and here they are seeing a ‘world that is altered by AI and by filters,’ but that’s not always disclosed, right?” she said. “And so everything looks perfect. This is going to affect a girl’s confidence.”

But for Grafland, a complete phone restriction is going too far and is counterproductive in aiding students’ in their own management of phone use.

“I think it puts kids into a situation where they don’t know how to regulate their phone use without someone taking it away from them,” she said.

The dispute over the upcoming phone policy is not likely to end soon, but all sides agree that the students’ best interests should be prioritized.

“It’s not black and white. I see both sides at the end of the day,” Quriashi said. “I think you kind of have to go with the science and what’s best for girls long term, not just what we want short term.”

![[GALLERY] Walking in (Downtown) Memphis](https://stmarystatler.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E1DAD3FE-E2CE-486F-8D1D-33D687B1613F_1_105_c.jpeg)