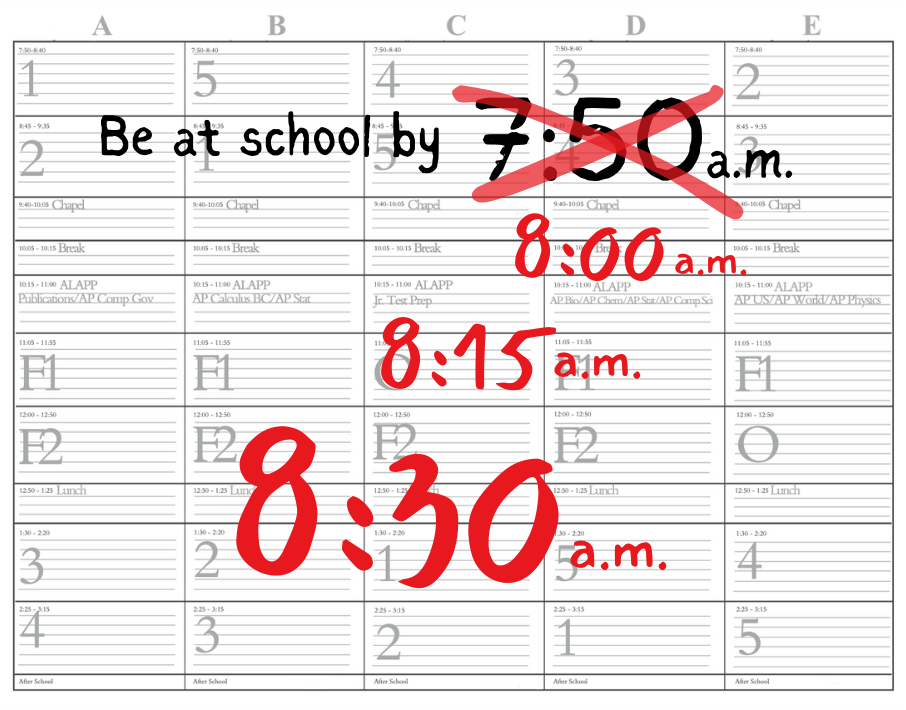

The math is tricky. The school day at St. Mary’s upper school starts at 7:50 a.m. To get to school at 7:45 a.m., a student with a 15-minute commute needs to leave their house at 7:30 a.m. To make that departure time, they need to wake up at 7:00 a.m. and get ready in 30 minutes. To get the recommended nine hours of sleep, they have to go to bed at 10:00 p.m.

The problem? Teenage circadian rhythms make it difficult for them to fall asleep before 11:00 p.m.

Why You’re Sleepy

It isn’t easy for St. Mary’s students to get a good night’s sleep. Sophomore Hannah Loden encounters this struggle daily, regularly going to bed between 1:00 and 2:00 a.m.

“On school nights, I probably get five hours [of sleep],” she said. “Maybe five hours, that’s good for me. On weekends, I’d say maybe eight to 10 hours.”

Getting out of bed in the morning proves hard for Loden because of her early wake-up time of 6:00 a.m.

“I set multiple alarms,” she said. “When I set my alarms, I set a timer, and so I usually end up hitting snooze like five times. There’s probably five to six alarms, and they’re all five to 10 minutes apart. I actually usually get out of my bed at 6:30 in the morning, and then I rush to get everything done because I’m tired. It [takes] me so long to actually make myself get out of the bed.”

It is normal for teenagers to feel tired that early in the morning. According to the National Institute of Health, teenagers’ ideal wake up time is 8 a.m, but by that time, St. Mary’s students have already been in class for 10 minutes.

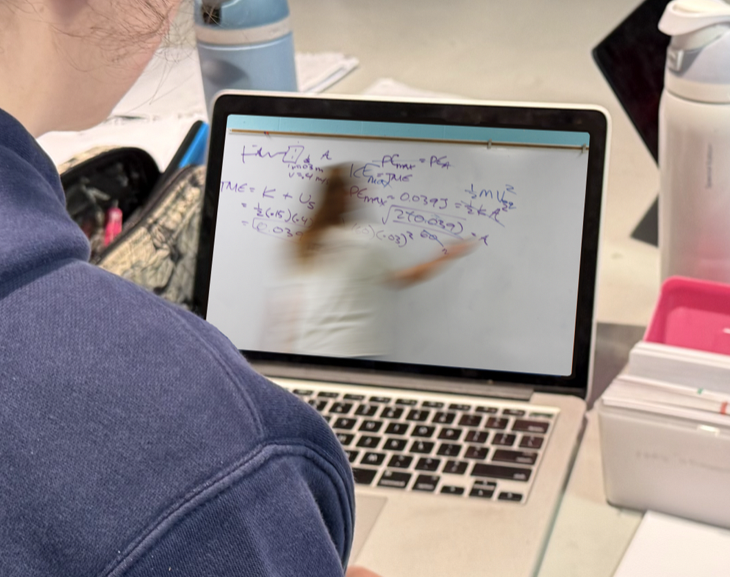

Unfortunately, the type of sleep that is potentially cut short in the morning is some of the most necessary for learning, according to Phyllis Payne, the implementation director at School Start Later, which encourages delayed starts.

“In the morning, the last sleep of the night that we get is the sleep that is most concentrated with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is when short-term memories are turned into long-term memories,” Payne said. “That’s basically the definition of learning. [REM] is also important for the repair of muscles and emotional response and sort of being able to be optimistic. There’s a lot of interconnected elements that happen during that portion of the night, and when you have to get up early for school, that last portion of your sleep cycle is cut off.”

More sleep equals a better memory, an easier wake-up and better mental health. But homework, extracurricular activities and family responsibilities can pile up, making it more difficult to get to bed at an hour that would allow for a full night’s sleep.

For Loden, it’s theater that pushes back bedtime.

“I’m very involved in theater, and I work backstage,” Loden said. “So four times a year, I’m involved in a production, which usually takes up lots of my time after school, especially during tech week, which is the week right before a production starts. We’re usually at school until 8:00 p.m., and I end up getting very little sleep because of that.”

Those missed hours have consequences. Getting fewer than seven or eight hours of sleep per night can negatively affect physical and mental health, making it harder to complete daily tasks and perform well in academic environments. According to the CDC, people receiving inadequate sleep also have increased odds of frequent mental distress.

To complicate the issue, women on average need 11 more minutes of sleep than men, which may not seem dramatic, but it’s significant. Without adequate sleep, they’re at a higher risk of the negative impact of sleep deprivation.

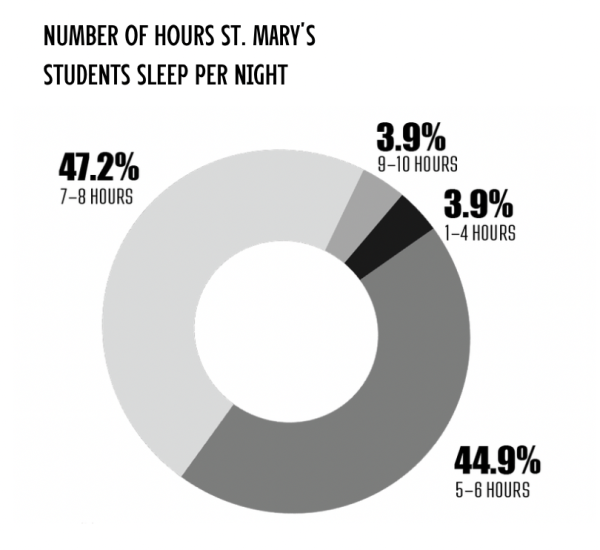

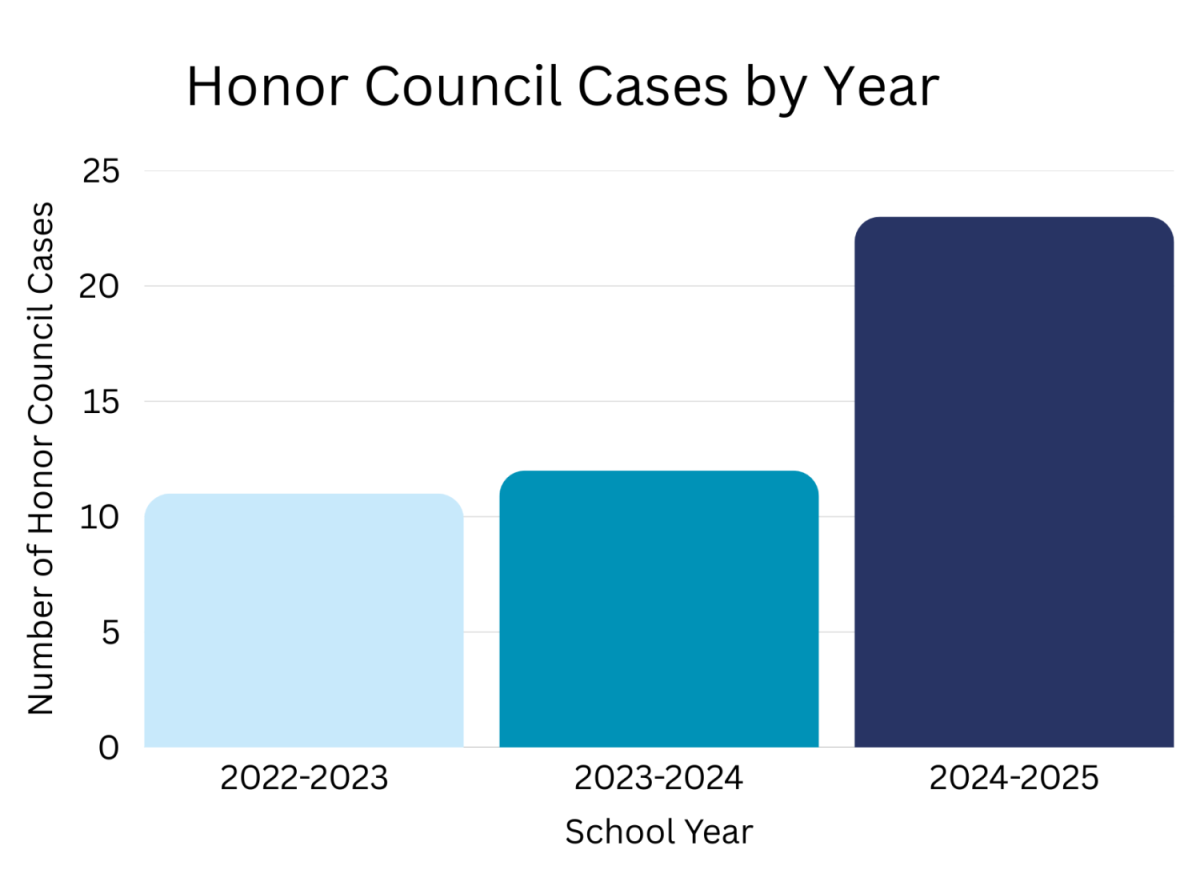

These health effects are especially evident in teenagers. John Hopkins Medicine recommends at least nine hours of sleep per night for teens, but according to a survey Tatler conducted, only 4% of the 127 students who responded report regularly getting that amount. Forty-seven percent of students said they get seven to eight hours of sleep a night, and around 45% said they sleep for five to six hours.

Compared to the rest of the country, this is typical. Nationally, teenagers tend to get around seven hours per night.

This low number, which is around two hours under the recommended amount, can’t be corrected by sleeping in on the weekend.

“We don’t ask kids not to eat during the week because there’s not enough time for lunch and binge eat on the weekend to make up for it,” Payne said. “But when they start school before your brains and bodies are ready to be awake, in effect, they’re saying it’s okay, you can catch up on the weekend. Sleep doesn’t work that way. Our brains and bodies don’t work that way.”

Sleep functions on a 24-hour cycle. If 63 hours is the ideal amount of sleep students need per week, it has to be broken into seven days to feel effectively energized every day. Waiting until the weekend to make up for the sleep deprivation caused by the school week is not an effective solution. Students receive sleep’s natural benefits only if they get the proper amount at the right time.

Just going to bed earlier, a frequent suggestion, poses problems as well.

“The hormones that make you feel sleepy and able to stay asleep are released later in the adolescent body, and that means it’s harder for you to fall asleep early,” Payne said. “A lot of adults will say, ‘Well, just put them to bed earlier,’ but you can be in bed in the dark and not able to sleep.”

This is something Junior Leighton Visinsky knows not only from experience but also from having studied adolescent sleep patterns in a psychology class.

“If I get my homework done at 8:00 [p.m.], I’m not going to bed at 8:30 because it’s just not how your body works,” she said. “If I was 7 years old and I got my homework done at 8:00, I’d probably go to bed at 8:30. But because of the change in your circadian rhythm, it’s just more natural to go to sleep later and wake up later.”

Unfortunately, many current school times are not based on what is natural for high schoolers.

Start Times: Past and Present

Schools didn’t always start this early. For most of the 20th century, high schools typically started around 9:00 a.m. Earlier start times emerged in the 70s and 80s when school districts tried to cut costs and reduce the number of buses on the roads by staggering starts.

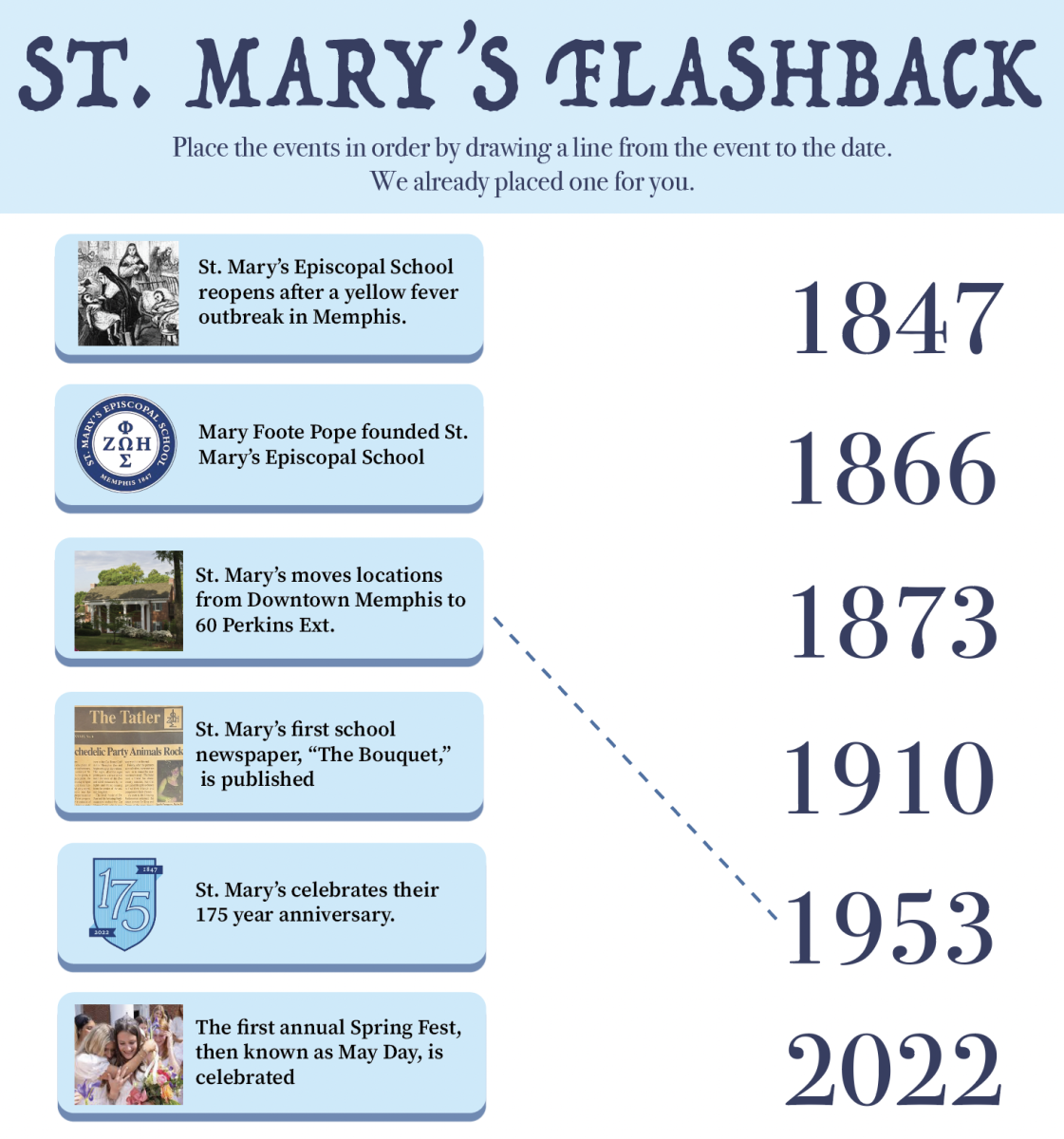

St. Mary’s start time didn’t change for this reason, but it also used to be later. According to St. Mary’s Historian Patti Ray, classes started at 8:15 a.m. up until 2005.

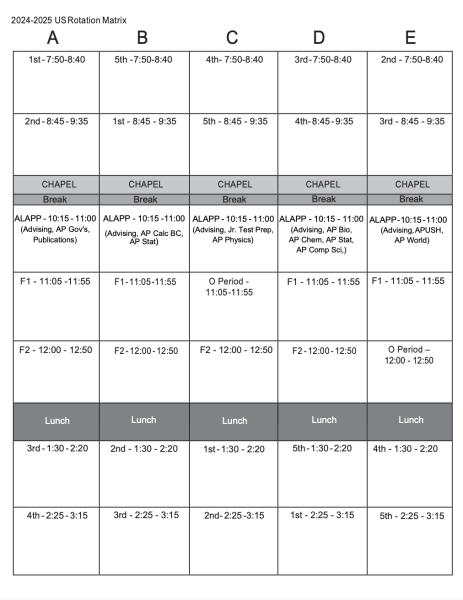

“[In 2005], we created the schedule that included ALAPP [daily free periods] and a little more time in chapel,” she wrote in an email. “Basically, the same schedule that you have now. We moved the starting time to 7:50 [a.m.] in order to accommodate ALAPP and additional time in chapel.”

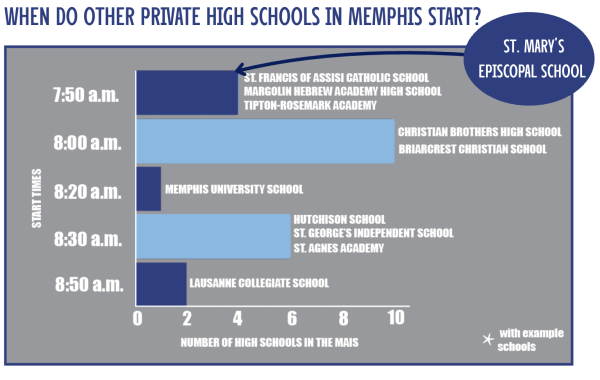

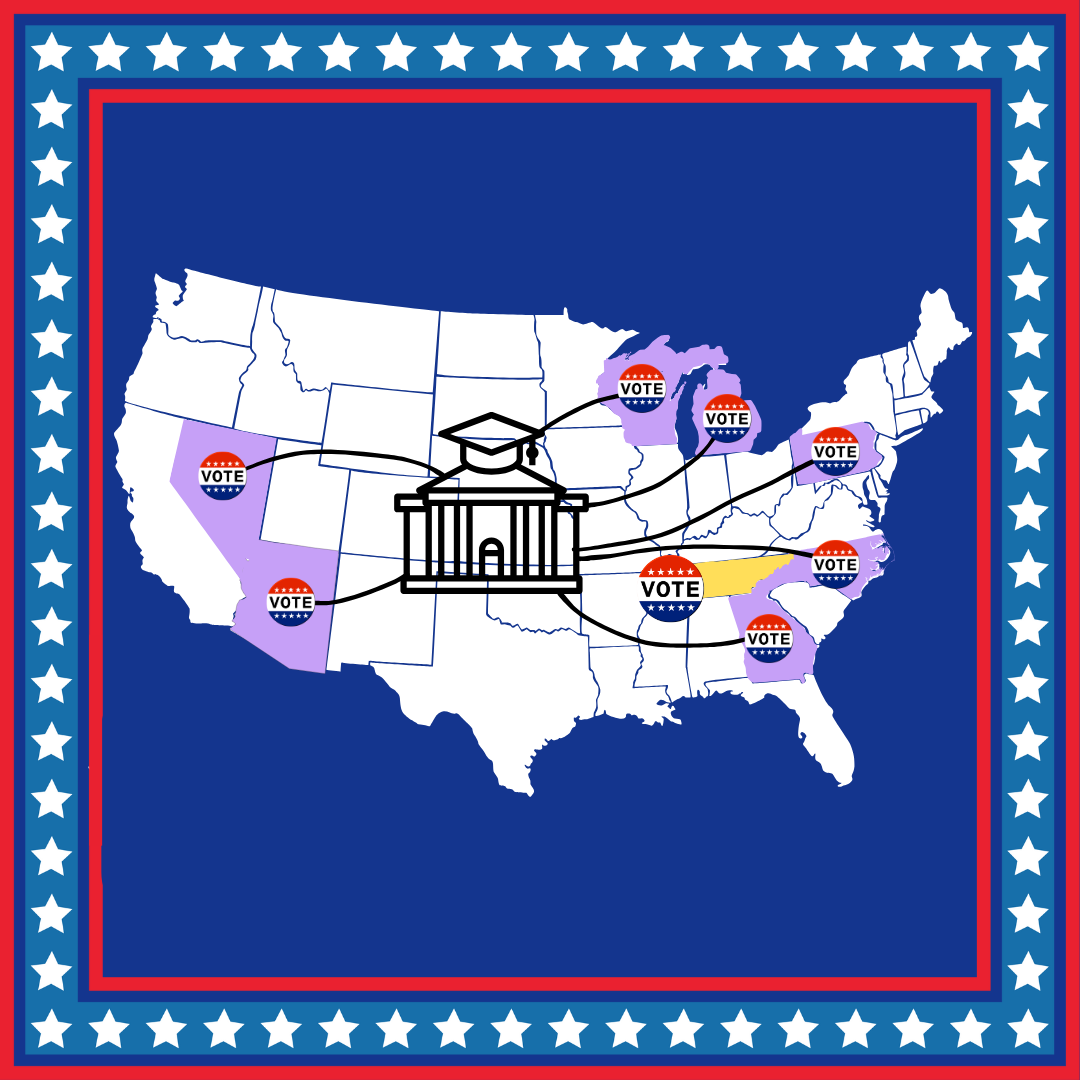

With its current schedule, St. Mary’s is in the 40% of high schools in the nation that now start before 8 a.m.. But across the country things are changing as more and more schools are letting students sleep in. California and Florida have passed laws that prohibit school districts from starting school earlier than 8:30 a.m., a time based on the recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In Tennessee, a similar bill was passed in the Senate in 2022 but did not make it to a vote in the House. The bill was sent to “summer study” by the House K-12 subcommittee, but no further action has been taken.

If it were to be signed into law, the shift to a later start could have significant payoffs. Research conducted at the University of Washington concluded that changing school start times to nearly an hour later resulted in an average of 34 minutes of extra sleep for students and improved their grades by 4.5% on average.

Locally, many private schools have already adopted later start times. Tatler surveyed the members of the Memphis Association of Independent Schools, to which St. Mary’s belongs, and of the 23 schools that responded, eight schools start at or later than 8:30 a.m. Included on that list are Hutchison School, St. Agnes Academy and Lausanne Collegiate School, which has an 8:50 a.m. start time. According to the survey, only three other schools start at 7:50 a.m. – St. Francis of Assisi Catholic School, Margolin Hebrew Academy High School and Tipton-Rosemark Academy. No school that responded to the survey starts earlier.

Albert Throckmorton, St. Mary’s head of school, said he was surprised to hear that so many local peer schools had later starts, but it’s an idea with a lot of support from the student body.

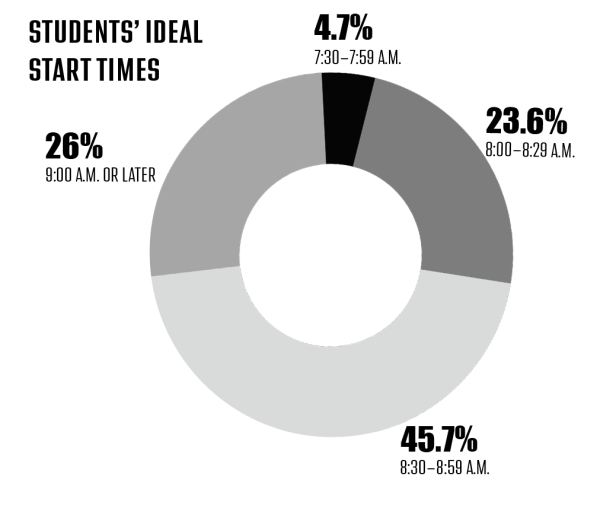

Ninety-five percent of students who responded to the Tatler survey said they would support a later start time. Around 46% of students said their ideal start time would be 8:30 a.m., and around 26% of students supported a start time even later than that.

Obstacles to Change

But starting later would require a substantial shift in the school schedule – a shift that could jeopardize how the current school day functions.

Throckmorton pointed out that there are many considerations that go into structuring a school day and many more questions than answers at this point.

“There are trade-offs,” he said. “There are trade-offs, and there are a lot of questions, so all I can give you is categories of questions. There’s working parents, chapel and lunch. Does [a later start time] affect a rotating schedule, free time in the day and our ability to schedule all the after-school and athletic times? Those are questions we’re looking at as we’re looking at student health and sleep.”

He said that at the moment the administration is working on solving another scheduling challenge by aligning the middle and high school schedules, which are currently different.

“We’re trying to get the middle school and the upper school on compatible schedules so that we can share teachers,” he said. “If we were to finally have achieved that, and then to change the upper-school schedule without the middle-school schedule, then we’re solving one problem that may be a more important problem.”

It gets complicated. When we think about pushing back the school’s start time, we have to think about what that means for the end time.

A later start time does not necessarily have to mean a later end time, but if it did, that would potentially complicate many after-school activities, including sports, theater and other co-curriculars.

If our end time stayed the same, free time during the day might need to be reallocated. ALAPPs, the daily 45-minute advisory periods dedicated to extra AP classes, publications, meetings and homework, and O periods, biweekly free periods, might need to be shifted or eliminated.

“We intentionally build everything into the school day,” Head of Upper School Lauren Rogers said. “So at many institutions that have abbreviated school days or move the school day later, that means that they’re having student clubs and organizations meet in the morning or meet after school. The schedule that we live at St. Mary’s is one where we have an O period for your organizations to meet. We have time built in for students to manage a lot of the external demands of their lives.”

Rogers points to this free time as first on the chopping block if there were to be a revamp of the schedule.

“I think the piece that is the most fluid in our upper-school schedule is the organizational time that we’ve built,” she said. “That is a place where things could potentially look different.”

A few students who responded to the survey suggested eliminating St. Mary’s daily 30-minute chapel service as a way to gain more time for sleep. However, Rogers was quick to say that the tradition is here to stay.

“St. Mary’s Episcopal School has always done one thing, and that is chapel, daily chapel,” she said. “That’s been a cornerstone of the school’s identity, a corner piece of who we are. I think when we talk about chapel and its role in the school day, that’s a pretty set firmament.”

If the conversation about a later start time were to happen, Throckmorton said he wants to research schools with similar traditions to preserve St. Mary’s culture.

“We need to look at schools that are dedicated to their chapel because I really want to support student health, but I also want to support our school culture,” he said. “I think our school culture is very much missionally tied to chapel.”

Visinsky isn’t eager to cut any free time during the school day, either.

“I’ve actually thought about this a lot, and I think there’s not necessarily something that the school would be happy with taking out,” she said. “I don’t think you can take out chapel, I think ALAPPs are important for clubs and APs. O periods are important just for a break in life.”

Parents’ schedules present another complication. With a later start time, parents would have to potentially accommodate a change in drop-off times, not an easy task for working families. Payne has encountered this problem before but believes it can be overcome.

“Parent and adult schedules are always a complication that has to be figured out,” she said. “If your priority is adult convenience, then that’s one thing. But if your priority is doing what’s good for kids, then [a later start time] is what you do. There are ways to overcome that challenge. If there’s any opportunity to carpool with other students, [that’s a solution]. Some students [might] need to be dropped off at the time they’re being dropped off now, so ask is that possible? Could they have access to the cafeteria to eat breakfast or the library to sit and do homework? A lot of other private schools start at 9:00 a.m., so there must be ways for parents to transport their kids.”

Throckmorton recognizes this possibility, but also acknowledges its complications.

“I mean, the bottom line here is, there is a way to [organize a] schedule,” Throckmorton said. “There’s probably a way… to schedule our day beginning at 8:30 a.m. and then we just have to say which trade-offs are inconvenient, and are there any trade-offs that are either non-negotiable or just add too many obstacles to either the teaching day or the operational day.”

One School That Made the Switch

St. George’s Independent School, an Episcopal school in Collierville, Tenn., is one that has made the shift to later start times while preserving free time and a time for chapel. In 2016, it introduced a rotating block schedule that starts at 8:30 a.m. most days, ends at 3:15 p.m. and also includes a daily chapel period and an open period for clubs and meetings similar to ALAPP.

The biggest difference between their schedule and St. Mary’s is 70-minute classes compared to our 50-minute ones. Though St. George’s classes meet only three times a week, students have 210 minutes in each class per week. In contrast, St. Mary’s students meet in each class for 200 minutes per week.

Though St. Mary’s students might balk at an extra 20 minutes in class, Emily Metz, an upper-school history teacher who used to teach at St. George’s, said the 70-minute classes have their own benefits.

“I do not think I ever actually taught bell-to-bell, 70 minutes straight of me lecturing,” she said. “Nor do I think many of my colleagues who also have taught in a 70-minute schedule taught the full 70 [minutes]. I never felt like, ‘oh my gosh, this class takes forever.’ It was more of an opportunity to be able to do multiple different things in one class period surrounding the same topic for all different kinds of learners.”

St. George’s schedule also includes a 50-minute lunch and a daily free period at the end of the day similar to ALAPP. However, unlike our schedule, St. George’s students do not have frees similar to O periods. But they do have that late start.

Sophomore Gracley Barnett, a former St. George’s student, can recall the positive effects of her old school’s start time.

“[At] St George’s, I went to bed around the same time, but I didn’t have to wake up until 7:30 a.m.,” she said. “I got more sleep and then I wasn’t as tired for first period [at St. George’s]. I always feel like I’m really tired [at St. Mary’s].”

And she’s not the only one. According to our survey, 40% of students said they only sometimes feel well-rested at school. Thirty-five percent said they rarely feel rested.

Payne said she thinks addressing the problem of student sleep should be an immediate priority for schools, even ones faced with scheduling challenges.

“In effect, [administrators are] telling you is that all of those other things are more important than your sleep, and that’s a poor position for an administration to stand on,” she said. “Student health, your mental health, your academic performance, your sports performance and your enjoyment of activities is all linked back to getting good effective sleep.”

What You Can Do Right Now

St. Mary’s is not likely to see a schedule change soon, so what can students do to avoid the worst effects of sleep deprivation right now? Payne looks to a quality routine as a partial solution, even when you can’t get a full eight to 10 hours.

“We should all have a bedtime routine,” she said. “Have a regular bedtime to set yourself up to let your body and your brain know it’s time to sleep.”

Finding out an ideal bedtime takes experimentation, but there are sleep calculators to help determine a bedtime and a wake-up time that will not cut off any sleep cycles.

Let’s Sleep!, an organization promoting healthy sleep, generated a database with information specifically catered to healthy sleep habits for students. They recommend against taking prolonged naps, hitting snooze in the morning and drinking caffeinated beverages too late in the day.

Rogers also recommended an additional method for prioritizing sleep – thinking ahead and planning a class schedule that takes sleep needs into account.

“When planning out academic schedules, students need to sit and think and reflect on the demands that [they’re] asking of [themselves], including rest and sleep,” she said.

St. Mary’s 7:50 a.m. start is early. That is certain. But it could be worse. Many public schools in Memphis, including our neighbor, White Station High School, start at 7:15 a.m. every single morning.

Louise Lawhead contributed to this story.

![[GALLERY] Walking in (Downtown) Memphis](https://stmarystatler.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E1DAD3FE-E2CE-486F-8D1D-33D687B1613F_1_105_c.jpeg)