At first Sandy Kozik couldn’t believe it.

Memphis theater company Friends of George’s, on whose board Kozik serves, had just won their hard-fought effort to strike down the 2023 Tennessee drag ban.

He and his group learned of their victory the day before the Memphis Pride parade, and the news made the parade even more celebratory.

“People had spoken up in the community, so there were many people who were excited,” he said. “It was really special to know that we had a… small part in history.”

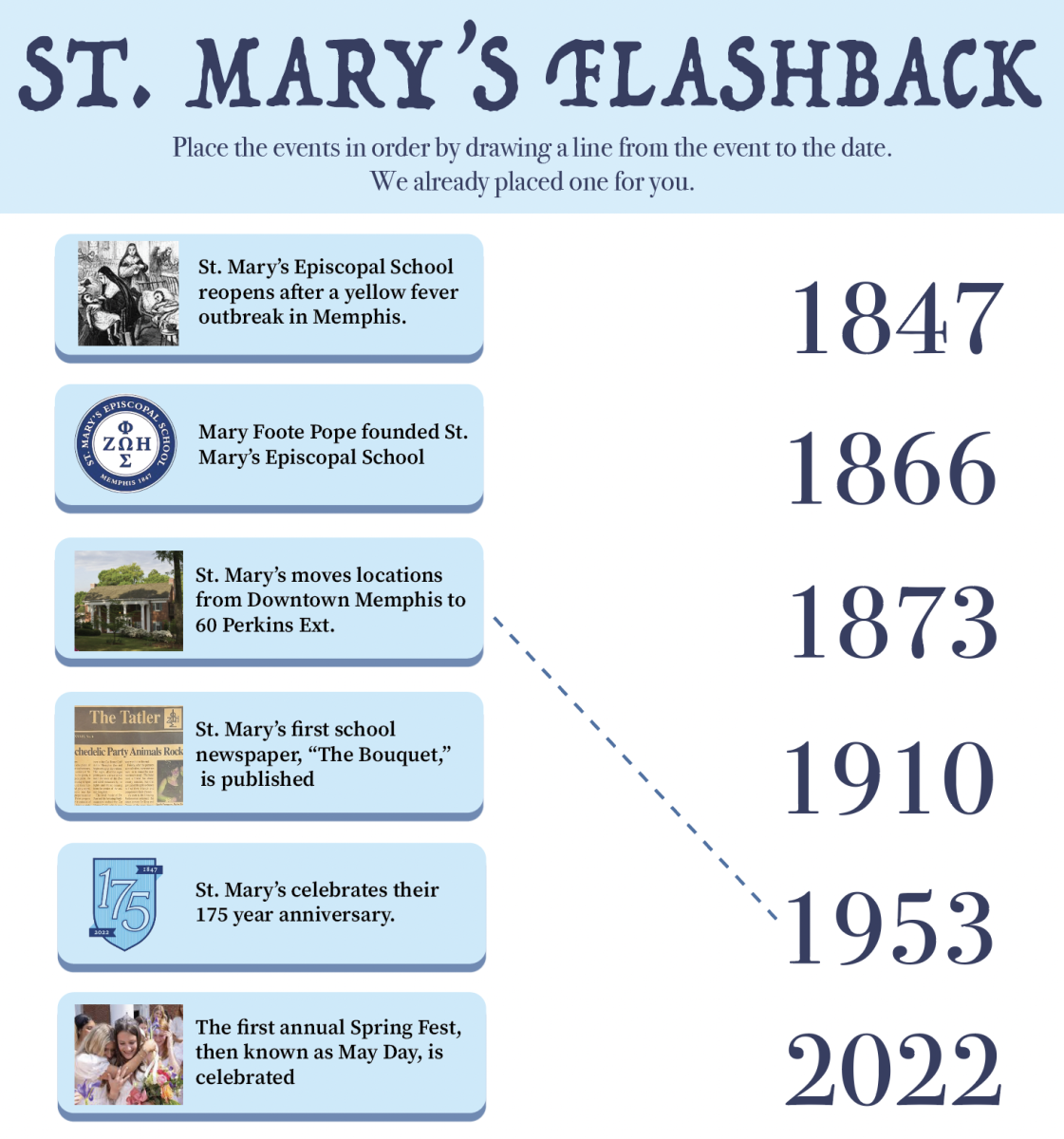

In 2023, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed into law a ban restricting drag performances in Tennessee. The bill was set to take effect in April. However, Memphis-based theater troupe Friends of George’s successfully filed a lawsuit against the state and won. Federal Judge Thomas Parker struck down the bill as a violation of the First Amendment.

If passed, the drag ban would have criminalized “adult cabaret entertainment” on public property or in any location where it could be seen by minors. The ban defined “adult cabaret entertainment” in one aspect as entertainment by “male or female impersonators.” In this sense, the ban’s vague wording could have potentially criminalized anything from Halloween costumes to cross-dressing in school plays.

Attempts to criminalize drag, the art of dressing exaggeratedly as another gender, are not a new occurrence in the United States.

Drag’s roots can be traced back to the ancient Greeks, who specialized in plays where men dressed up as female characters. Perhaps the most famous example of drag is Shakespeare’s plays, where male actors played female characters in plays that frequently toyed with societal gender expectations.

Later, during the Harlem Renaissance in the early 20th century, drag balls gained prominence in the emerging LGBTQ community, despite police raids and arrests aimed at suppressing them.

The 1960s and 70s marked a turning point in the fight for LGBTQ rights. In 1969, the Stonewall Inn riot, where patrons of a gay bar fought back against a police raid, brought attention to the movement towards acceptance. The 21st century has brought more acceptance of drag in mainstream culture, with episodes from the television show RuPaul’s Drag Race reaching a total of 1.3 million people across the US.

Growing up queer in Mississippi, Memphis drag queen Deejay Rollison (stage name Tiffany Minxx) always felt a pull towards stereotypically feminine things. When he discovered RuPaul’s Drag Race in 2014, he realized there was an avenue to channel his interests.

“Drag, for me, is the highest form of expression [because] it takes parts and elements of yourself that are maybe not standard for everyday life and allows you to live through them… in a fantastical kind of way,” he said. “Drag is all about love and storytelling and expression, and I think because of that, drag means so much to so many different people.”

When he first heard about the ban, Rollison only felt shock.

“I’ve always been an advocate for social justice and change,” he said. “But it was a very different experience when the thing that was being attacked was the thing you are a part of.”

Friends of George’s was in the midst of producing a theater production when the ban was announced. Not only did the ban threaten to put an end to something that brought the group joy and ruin the hard work they put into the theater production, but it would also jeopardize their First Amendment rights.

“[The ban would] take our choice away,” Kozik said. “Friends of George’s [supports] the First Amendment.”

Kozik also believes that the ban was motivated by fear and serves as a distraction from larger issues.

“I think what motivated the ban was it’s something unknown, it’s fear,” Kozik said. “It’s also a way to mask other things that are more important that society needs to be worrying about.”

The ban specifically targets children, described as “a person who is not an adult,” as the focus. However, Kozik considers the concern that seeing drag will be harmful to minors completely unfounded.

“People… went ‘oh my goodness, our children will see [drag] and not understand,’” he said. “Whereas children… usually get it way before their parents. It’s like seeing Cinderella at Disney World or Ronald McDonald at McDonald’s. It’s a fantasy character, and they’re like, ‘oh, it’s not really real, but it sure is cool’.”

Taylor Ragan, the performing arts teacher at St. Mary’s, has worked in theater communities for over 10 years. She believes that in theater, experiencing new things should be a way to learn.

“[The ban is] a limitation of your freedom – your freedom of expression, your freedom of speech,” said Ragan. “If you start there, what’s next?”

“The thing that is so amazing about theater and about art in general… is that it’s meant to create dialogue,” she said. “When you leave, you are supposed to think and reflect on… what you just saw and how that either affects your life or informs everyday aspects of your life… [the unknown] should create an opportunity to learn and grow.”

The ban attempt seemed to have the opposite effect of what its writers intended. Their efforts to overturn the ban brought Friends of George’s national attention. Kozik recalls the group making national news, from NBC to Time Magazine and Rolling Stone. Back in Memphis, this attention meant a wave of new audience members wanting to see drag for themselves. Over time, Rollison also discovered that the ban attempt brought the drag and queer communities closer together and drew out more support between drag queens.

“[The ban] didn’t make us cower,” Rollison said. “It made us come forward.”

![[GALLERY] Walking in (Downtown) Memphis](https://stmarystatler.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E1DAD3FE-E2CE-486F-8D1D-33D687B1613F_1_105_c.jpeg)